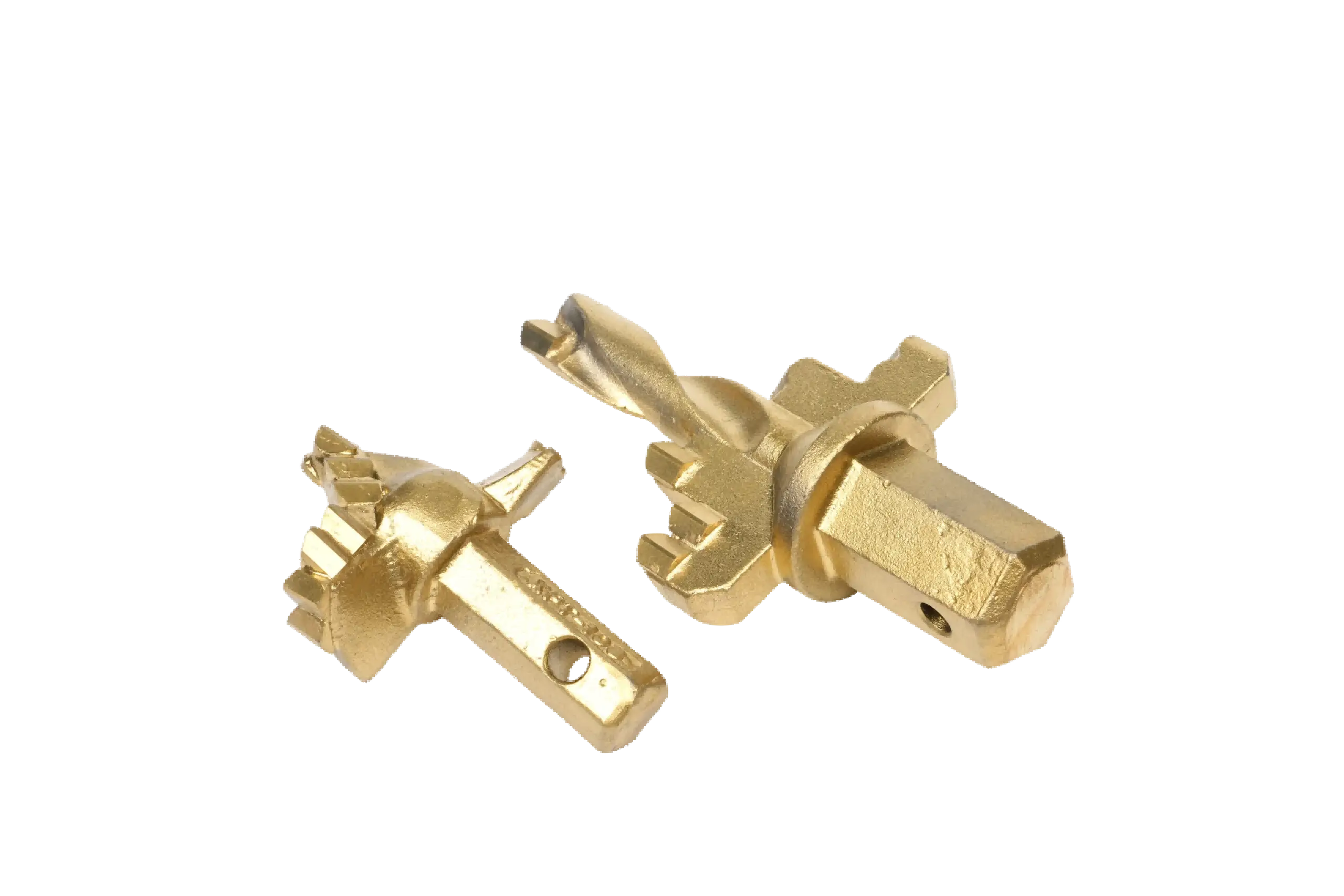

Hot forging is one of the core technologies in metal plastic processing. It applies external forces to a metal blank, causing it to undergo plastic deformation above the recrystallization temperature, ultimately yielding forged parts with the desired shape, size, and mechanical properties. This process can significantly improve the metal’s internal microstructure (e.g., by refining the grain size and eliminating casting defects), enhancing the strength, toughness, and fatigue life of forged parts. It is widely used in high-end equipment such as aerospace, automotive, and engineering machinery.

I. Core Principles of Hot Forging

The essence of hot forging is to utilize the properties of metals—their increased plasticity and reduced deformation resistance at high temperatures—to overcome the interatomic bonds within the metal through external forces (such as pressure and impact), resulting in permanent deformation of the blank. Its key principles include the following:

1. Recrystallization softening effect: When metal is heated to the recrystallization temperature (approximately 800-1250°C for iron alloys and 300-500°C for aluminum alloys), the work hardening caused by deformation is offset by dynamic recrystallization, allowing the blank to sustain large deformations without cracking, significantly reducing the external forces required for forging.

2. Microstructure Optimization Mechanism: Hot forging can break down defects such as coarse grains, porosity, and pores in metal billets (especially cast billets), aligning the metal’s streamlines (the direction of atomic arrangement) with the load-bearing direction of the forged component, thereby matching the component’s actual load-bearing requirements (e.g., optimizing the load-bearing direction of crankshafts and gears).

II. Key Elements of the Hot Forging Process

Successful hot forging requires precise control of four key elements. Any deviation in any of these elements can result in forging failure (e.g., cracks, dimensional deviations, or substandard performance):

l Heating Temperature: This temperature must be between the “initial forging temperature” (the lowest temperature for optimal metal plasticity) and the “final forging temperature” (a temperature below the recrystallization temperature that results in work hardening), with significant differences for different metals.

l Heating Rate: This temperature must match the metal’s thermal conductivity (e.g., high-carbon steel has a slow thermal conductivity and requires slow heating).

l Deformation Rate: This requires a balance between efficiency and quality. Impact loads (e.g., hammer forging) require high speeds and are suitable for simple parts; static pressure loads (e.g., press forging) require slow speeds and are suitable for complex parts.

l Cooling method: Select the method based on the forging material and performance requirements (e.g., air cooling, pit cooling, furnace cooling).

I. Typical Hot Forging Process

The complete hot forging production process involves three stages: pretreatment – forging – post-processing. The specific steps are as follows:

1. Blank Preparation

Material Selection: Select metal materials (e.g., structural steel, aluminum alloy, titanium alloy) based on the forging performance requirements. Rolled or extruded billets are preferred to reduce internal defects.

Cutting: Cut the metal raw material into billets of specified length and weight using sawing, shearing, or gas cutting, ensuring a weight error of ≤5% to avoid missing or excessive material in forgings.

Surface Cleaning: Remove scale, rust, or oil stains from the billet surface (usually using sandblasting, pickling, or wire brushing) to prevent impurities from being pressed into the forging and causing inclusion defects.

2. Heating Process

Charging: Place the cleaned billets into a heating furnace (e.g., resistance furnace, induction furnace, or gas furnace), ensuring that the spacing between the billets is ≥10mm for uniform heating. Heating and Holding: The temperature is raised according to a pre-set heating curve (e.g., 45 steel: room temperature → 600°C (slow) → 850°C (constant) → 1180°C (hold for 30 minutes)). Ensure that the core temperature of the billet reaches the initial forging temperature, and that the temperature difference between the inside and outside of the billet is ≤50°C.

Out of the Furnace: The heated billet is quickly transferred to the forging equipment using clamps or a robotic arm (transfer time ≤30 seconds to prevent excessive temperature drop).

3. Forging Process

Pre-forging: Initially deform the billet (e.g., upsetting, drawing), adjusting its shape to approximate the die cavity (reducing deformation resistance and die wear during final forging).

Final Forging: The pre-forged billet is placed in the final forging die, and external forces (e.g., hammer impact, press) are applied to ensure that it fits the die cavity perfectly, achieving the final forging shape (dimensional tolerance within ±0.5mm). Trimming and Punching: A press or punch is used to remove flash (excess metal that overflows the die during forging) and sliver (residual metal in the center of a hole in a forging) from the edges of the forging to ensure a clean appearance.

4. Post-Processing

Cooling: The forging is cooled according to the specified cooling curve (e.g., 40Cr steel forgings: air cool to 600°C after final forging, then quench to room temperature) to avoid internal stress.

Heat Treatment: Tempering (quenching + high-temperature tempering), normalizing, or annealing are performed based on performance requirements to improve the forging’s hardness, toughness, and processability (e.g., gear forgings often require tempering, with a hardness of 220-250 HB).

Surface Treatment and Inspection: Forgings are sandblasted or painted (for corrosion protection). Non-destructive testing (e.g., ultrasonic testing, magnetic particle testing) is performed to detect internal cracks, inclusions, and other defects. Dimensions and mechanical properties (tensile and impact testing) are also randomly inspected.

II. Main Classifications of Hot Forging Processes

Depending on the forging equipment, hot forging can be divided into the following four categories, with significantly different applications and characteristics:

l Hammer forging: Utilizes the impact force of a forging hammer (air hammer, steam hammer) to deform the blank. Advantages include fast deformation speed and suitability for simple forgings (such as crankshafts and connecting rods). Disadvantages include high vibration and low forging precision (dimensional tolerance ±1mm).

l Press forging: Utilizes static pressure forging using a mechanical press (crank press, hydraulic press). Advantages include stable load, high forging precision (tolerance ±0.3mm), and suitability for complex parts (such as gearbox housings). Disadvantages include lower production efficiency than hammer forging.

l Diameter forging: A die (diameter) is placed on a free-forging machine. Combining the flexibility of free forging with the precision of die forging, it is suitable for small-batch, medium-complexity forgings (such as agricultural machinery parts) and offers lower costs than full-scale forging.

l Specialty hot forging: This includes isothermal forging (maintaining the same temperature between the billet and the die, suitable for difficult-to-deform materials such as titanium alloys and high-temperature alloys) and radial forging (using multiple hammers to apply radial pressure, suitable for long-axis forgings such as gun barrels). These are primarily used in high-end equipment.

III. Applications of Hot Forging

Due to their excellent mechanical properties, hot forgings are the preferred choice for components subjected to heavy loads, impacts, or complex stresses. Typical applications are as follows:

l Automotive: Accounting for over 60% of all hot forgings, these include engine crankshafts, connecting rods, gears, transmission synchronizer rings, and control arms for chassis suspension systems (requiring high strength and fatigue life).

l Aerospace: Used in aircraft landing gear (300M steel hot forgings) and engine turbine discs (high-temperature alloy isothermal forgings), requiring reliability under extreme temperatures and loads.

l Engineering Machinery: Excavator bucket teeth, hydraulic cylinder piston rods, and crane hooks (requiring high hardness and wear resistance).

l Energy sector: Wind turbine main shafts (42CrMo steel hot forgings) and nuclear power pressure vessel flanges (low-alloy steel forgings) require fatigue and corrosion resistance.

IV. Hot Forging Process Development Trends

With the increasing precision and performance requirements for forgings in high-end equipment, hot forging technology is developing in the following directions:

1. Intelligentization: Introducing industrial robots to enable automated loading and unloading of billets, intelligent furnace temperature control (AI algorithms optimize heating curves), and online inspection of forging dimensions (machine vision), reducing manual intervention.

2. Near-net-shape: By optimizing die design and forging parameters, forging dimensions are brought close to the final product (for example, gear forgings require no subsequent cutting or only fine grinding), reducing material waste and production costs.

3. Greening: Utilizing induction heating (energy consumption is 30% lower than gas furnaces), waste heat recovery systems (using waste heat from forging cooling to preheat billets), and reducing oxidation burns (using protective atmosphere heating, such as nitrogen or hydrogen) to minimize environmental pollution.

4. Material expansion: Develop special isothermal forging and low-temperature hot forging processes for lightweight and high-strength materials such as titanium alloys and magnesium alloys to meet the lightweight needs of new energy vehicles and aerospace.